This article was first published on The Conversation on 3 July 2017. You can view the original article here.

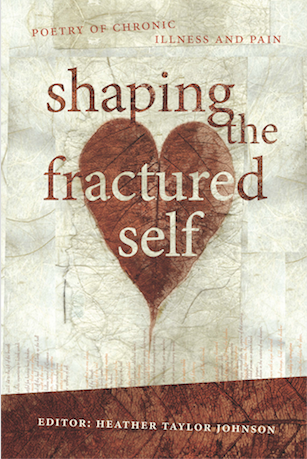

Heather Taylor Johnson, editor of Shaping the Fractured Self: Poetry of chronic illness and pain will be in Perth for the WINTERarts Festival at the end of this month. Enrol in her writing masterclasses 'The Poetry of Bodily Trauma' and 'The Prose of Bodily Trauma' at the links.

There are several ways into the book Shaping the Fractured Self: Poetry of chronic illness and pain, edited by Heather Taylor Johnson. And there are many uses it might serve in the multiple worlds of poetry and the even wider worlds of medicine, therapy, sociology and life writing, to name just a few.

I picked it up expecting some dour texts about illness, pain, death and how some survivors have managed lives of being half alive, but it turned out to be a book I wanted to share with others. It had parts I found myself underlining, and not only could I not put it down, I kept skipping around in it, eager to read more of the stories, reflections and poems of these 28 poets.

Illness has been a powerful theme and provocation for writers. There have been in my reading, Vincent Buckley’s hard won poem of his father’s illness, Stroke, many startling poems by Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, Hilary Mantel’s memoir of pain, Giving Up the Ghost, Virginia Woolf’s essay On Being Ill, Stefan Zweig’s only novel, Beware of Pity, and many, many other works.

This is not the first anthology to pair illness and poetry. Johnson recounts in her introduction that the great American anthology, Articulations: the Body and Illness in Poetry, edited by Jon Mukand, was an inspiration for this Australian project. The connection we make between poetry and illness is an old one too. One of the more recent studies attempting to reinforce this perhaps fundamentally romantic connection was Kay Redfield Jamison’s Touched with Fire: manic depressive illness and the artistic temperament (1993).

Using textual records, Jamison found a remarkably high number of Irish and British poets between 1705 and 1805 suffered from manic depressive conditions. My thanks go to Melbourne poet and surgeon, David Francis for uncovering this piece of medico-literary research. Johnson’s anthology, however, is not the kind that sets poets apart as differently made, differently brained, or strangely but beautifully ill and tragic. This anthology brings poets back in to the world of ordinary people faced with unexpected, often rare and chronic illnesses.

Each poet in this anthology is given two to four pages to write a small autobiographical piece on their illness, its rarity, its progression and treatment, and some history of their experiences of it. Then each poet is allowed three poems to show the several sides to their experiences and reactions.

The book would, I think, be equally satisfying to read for the small autobiographical essays, with the poems as means of enhancing the personal stories, or for the poems with the essays as enhancing insights into what the poems have been articulating.

It is rare to find poems simply repeating what was in the introductory personal essay. This means that the book can be as exciting to read for its literary, creative and cathartic value as for its value to (for example) medical students curious about how illness shapes the self and how the medical profession is perceived and experienced by the ill.

What are these illnesses then? The much-honoured and deeply accomplished poet, Peter Boyle, writes of the onset of polio when he was barely three years old in 1954. After years of paralysis and treatment, by 1968 Peter Boyle was dux of Riverview College in Sydney and he was writing poetry. I have been reading Peter Boyle’s poetry for years, sensing his acquaintance with pain and illness, but not knowing explicitly what his story was.

In two and a half pages, Boyle writes simply and intelligently and bravely of his life and how poetry works in it. Andy Jackson, another poet whose work I have enjoyed and admired for years, writes of inheriting Marfan syndrome from his father. Jessica Cohen writes of her fibromyalgia, a disorder caused by abnormalities in how pain signals are processed. Sophie Finlay suffers from postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a mysterious condition that involves a faulty bodily response to gravity.

Others suffer from the invisible but no less real and physical condition of mental illness. Gareth Roi Jones and Meg Dunley write of the more or less constant migraines they have suffered since childhood. Steve Evans and Susan Hawthorne write of their epilepsy. Heather Taylor Johnson has been diagnosed with Ménière’s disease, a condition resulting in severe vertigo.

Other conditions include a bulged disc as a result of rape, anorexia, transient global amnesia, chronic fatigue syndrome, the frightening condition of hyper-flexibility, MS, acromegaly and its complex consequences, temporomandibular joint pain, and Sjörgen’s syndrome. Most conditions are rare, some few of them are becoming more common, all of them require bravery, doggedness, resilience—and beyond all odds these poets expend much of their precious energy on being positive and creative.

Being poets, their illness cannot entirely define them, while at the same time it becomes clear that these illnesses have shaped them powerfully. Some poetry transcends illness:

If I was ceramic I’d be kintsukuroi,

Pottery which has been knocked,

Dropped, broken into shards then

Mended with gold or silver lacquer,

A delicate meander of liquid gold

Flowing into the breach …

(from Axiology by Anne M. Carson)

Sometimes the poetry brings brutally raw despair to the fore:

My brain is broken / that’s how it feels

But there’s no glue to fix it / only time and more time

Piles of pills / popped from their shells

Handfuls thrown down / tired throat accepts.

You better yet? / is the endless question

Yes, is the lie.

(from Yes, is the lie by Meg Dunley)

Then there can be dark wit combined with acute perception informing a poem:

on the road into town

our redneck neighbours

have a barren grassless

perennially overstocked

livestock paddock

dad & his mates call

the linger & die paddock

where there’s always

at least half a dozen

extremely unwell sheep

blighting the hillsides

with their lethargic

wanderings before

giving up & becoming

another bloated carcass

sometimes my brain

grazes there too

(the paddock by Gareth Roi Jones)

David Brooks offers a glimpse of not just the social life of the disabled, but how one feels to be positioned in a certain way in this world:

Four friends have called in the last two days

from London, Perth, Canberra, Corowa,

and all quite unexpectedly.

They worry about me, they say, and need to know how I am.

I’ve heard from none of them for months

and am touched, of course,

but the synchronicity unsettles me – some

ghost-in-the-works, maybe, or

mood passing over; not, hopefully, a

portent of imminent disaster. I’m

alright, I say, feeling

fitter every day, ribs

healed at last, no

fall for months, mood

as good as it could be on this bright, high-

winded mountain Tuesday with

Trump and Clinton engaged in their first

Presidential debate ….

(from Disabled Poem by David Brooks)

There is a lot to admire and relish in the poetry on offer in this book. Johnson is to be congratulated for putting together such an intelligent and brave and heartfelt and honest collection of poetry and mini-essays.

Finally, if there is one common theme running through this book, it is one that the book does not make explicit, and does not use as a justification for its existence. This theme is the alienation people regularly feel when subjected to interactions with doctors and subsequent medical treatment. I was shocked by the times that different writers remembered their doctors smiling at them as they delivered catastrophic news or devastating diagnoses.

No doubt these doctors were themselves distressed and confronted by the illnesses they had to discuss with patients, but my wish is that doctors might be trained to bring more awareness, more empathy, more professional self control and more understanding to their important roles.

If every medical student was given a copy of this book to read and discuss and re-read, we might, we just might, have people reporting different stories of their encounters with the medical profession.