- Writing a biography is a big commitment to a single subject. How did you discover Aileen Palmer and when did you know you wanted to write her life?

It’s hard to pinpoint when I discovered Aileen Palmer. My subjects usually evolve from a variety of sources, often from previous research projects. I came across discussion of the Palmers in the correspondence between poet, Mary Fullerton, and Miles Franklin; Ida Leeson and Miles Franklin used to talk about them too (Miles was an excellent source of gossip about her literary contemporaries). There was a piece in Overland by Dorothy Hewett about the Palmer daughter who upset Vance and Nettie with her drinking and lesbian behaviour. A colleague mentioned there was an intriguing diary in the National Library archives, kept while Aileen was at university. I looked at that several years before I decided to write the biography, finding it fascinating but cryptic, but also discovering there was an extensive archive of her papers. Eventually I needed a project for an Australia Council grant and Aileen was the woman I chose.

- You write about remarkable women lost to history, such as Ida Leeson, Miles Franklin, Mary Fullerton, and Mabel Singleton. So why Aileen? What was remarkable about her?

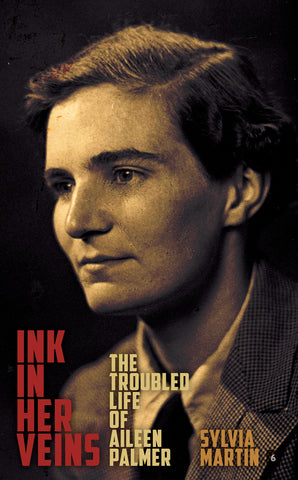

I need to go back to my principal research interest to answer this: exploring lesbian subjectivity and women’s friendship, looking at how women from the past might have understood their desires regardless of whether they labelled them. Archives fascinate me: reading letters and diaries, getting to know my subjects almost on a personal level, also exploring the contexts of their lives. Aileen’s university diary started my journey into her life. But I discovered so much more, that the woman known as ‘the tragic daughter’ of Vance and Nettie had been a brilliant child who wrote plays and novels, that she spoke several languages, that she was a communist who volunteered for the Spanish Civil War, that she drove ambulances in London during World War II. Her wartime diaries suggested relationships with women. She was a writer with a complex relationship with her well-known parents. What a story. How could I resist?

- What do you believe a biographer’s responsibilities are towards their subject? Did you ever feel inclined to protect Aileen? Did you want the complex truth to speak for itself? Did notions of ‘reputation’ or ‘legacy’ ever affect what you wrote?

I follow Hermione Lee’s dictum that ‘what we want from [biography] is a vivid sense of the person’. My theatre background helps me create my ‘characters’ while being true to their own voices, hence my weaving of Aileen’s own words throughout the book. I didn’t want to protect her but I always ask myself if including any detail about a subject’s life furthers the narrative in an ethical way. I wanted the complex truth to speak for itself and I tried to avoid being judgemental. For instance, I didn’t feel it was my position to diagnose Aileen’s ‘mental illness’ but I let her own voice and those of others be heard on this complex issue in order to let readers form their own opinions. I do think about legacy. In Aileen’s case, I wasn’t arguing that she was a neglected major poet, but wanted to reveal a brilliant and fascinating woman who was so much more than Vance and Nettie’s ‘tragic daughter’.

- Did you feel any differently about Aileen after researching and writing her life from when you began? How did your relationship with her evolve?

I went through many ups and downs during the more than seven years it took to write this book. Sometimes I thought I would never finish it. It was hard not to get sucked into the vortex, so to speak, of the misery of her later writings and I often felt overwhelmed by the sheer amount of material – the rewritten pieces, the lack of coherence, the cryptic diaries – but I was also inspired by some of her wonderful writing. It was hard to find a structure for the biography given that the first thirty years of her life were packed with activity and then there was the slow decline after her first breakdown. Once I found that structure, the writing became easier and gradually I became aware of the resilience she showed through those difficult later years as well as the sadness of them, for all her family.

- You have mentioned it was during your PhD that you started seriously considering what it means to be a feminist biographer. Could you expand upon this? What does being a feminist biographer mean to you?

My PhD was in Women’s Studies so I was immersed in feminist theory, poststructuralist theory, queer theory and so on. Books like Liz Stanley’s The Auto/biographical I made me think of the question of the author’s position in writing biography and how the conventional idea that biography is an objective recording of a life is impossible. We start to select from the moment we step into the archive or conduct an interview, choosing material that stems in some way from our own ideas and values. The lives we choose to write about are important; in my case, I don’t look for women who have necessarily achieved great things, but those whose lives have been devalued or neglected. I put myself in the picture and I become part of the biographical journey, making the process visible and on occasions commenting on it. I make it clear that this is one version of the life I am writing, not the version.